The Fifth Annual OutReach LGBTQ Pride Parade went off with no logistical problems on August 19, with hundreds of people marching and hundreds more lining State Street and the Capitol Square for the festivities.

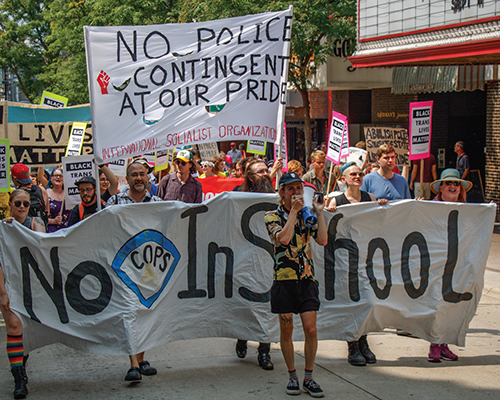

The lead-up to the event was anything but smooth, however. A group eventually calling itself the Community Pride Coalition protested the inclusion of official, on-duty law enforcement groups in the parade and began demanding that sponsors pull out of the event due to what was perceived as non-responsiveness and silencing on the part of OutReach LGBT Community Center, the parade hosts.

Just two weeks before the event, OutReach’s board voted unanimously to reverse course and withdraw the applications of MPD Pride (Madison Police Department’s LGBTQ employee group), as well as Sheriff Dave Mahoney, and the U.W. Police Department.

“Our community is facing complex, unprecedented times, where power is a fleeting commodity for our most vulnerable members, especially queer and transgender persons of color. In times like these it is crucial that we listen to those whose voices are not often heard in the mainstream,” their official statement read. “Those whose voices are silenced due to gender and sexual orientation, as well as the intersections of race, class, ethnicity, gender, ability, immigration status, age, and lack of institutional power, need us to amplify their voices.”

OutReach went on to invite any and all queer and allied law enforcement members to participate in the parade so long as they were “off-duty, unarmed, [and in] plain clothes,” which some of them ultimately did. The Madison Fire Department issued a statement saying they would boycott the parade in protest of the decision, though they had not yet submitted an application to march.

The decision immediately drew a firestorm of criticism from both within and outside Madison’s LGBTQ community, with intense arguments dominating social media for the weeks that followed. The issue seemed to highlight a stark but previously somewhat hidden divide within the community, though opinions have varied as wildly as there are individuals who identify as LGBTQ. Some conversations devolved into racist and transphobic attacks, while others represented the mixed emotions and deep personal conflicts around the problem.

At a rally following the parade, activist T. Banks took the stage and delivered a blistering rebuke of both OutReach and the white population of Madison’s LGBTQ community, alleging a lack of real allyship in the struggle for justice for queer and trans people of color.

“A white racist police, white supremacist, and white homophobic police presence still exists today in Madison,” Banks said. “It’s telling when the biggest white queer organization—that’s OutReach—took over three years to kick the cops out of Pride. OutReach had to battle whether or not to take the cops out of the Pride parade, in aid of its queer and POC community members. The police department is a bully. OutReach in its inaction…demonstrated their own racism within the board of directors and staff.”

OutReach has a paid staff of just 3.5, relying heavily on volunteers to run its operations. The organization took over putting on the parade in 2014, after several other groups started and sputtered in their efforts to create a long-lasting Pride event. The controversy resulting from this year’s decision to remove law enforcement from the parade itself has already resulted in the loss of several large donors to the center, threatening its ability to continue running the event, as well as its overall viability as an organization.

“The purpose of Pride is to remember the struggle that happened in Greenwich Village and at the Stonewall Inn,” Banks went on to say. “And that cops have never been Officer Friendly, even if they do identify as queer. Pride is no place for cops.”

Reactions from the crowd were mixed, with some hearty cheers and others booing, cursing, or just leaving the rally altogether.

How did we get here?

Discussions and disputes about police participation in LGBTQ Pride events are not new. The issue has come up time and again in cities large and small across the United States and Canada, with Toronto Pride making headlines this year for barring its local police from participating in the parade while in uniform or on duty, and controversies around the issue cropping up in New York and San Francisco as well.

In Madison, questions first came to the forefront after 2017 Pride saw a mandate by the city to increase the number of police on security detail. This came in reaction to events in Charlottesville, where white nationalists rallied and shot into a crowd of counter-demonstrators (killing one by driving a car into a crowd of peaceful protesters). OutReach also announced an active shooter training for volunteers.

The move galvanized many within the community already opposed to police at Pride, especially for queer and transgender people of color (QTPOC), who face disproportionately high rates of targeting and arrest at the hands of law enforcement, according to a study by the Movement Advancement Project.

The Wisconsin Transgender Health Coalition, a group of independent, grassroots activists based in Madison, brought their concerns to OutReach (which was at the time acting as the coalition’s fiscal sponsor). Jay Botsford, the group’s program director, had noted that they and others argued that the increased police presence would make people feel less safe, and that cops should be removed from the parade entirely.

“[OutReach] said it was too close, but that they would reevaluate for next year,” Botsford said. “Because they made that positive action at that point we said great, you’re going to do this intentional process for next year, you’re going to make sure that you’re speaking to people and getting the cops out of Pride, that’s fabulous. And then they never connected with us again. They never spoke to us. There were no public listening sessions, or if there were they were not well publicized.”

One such session was held shortly after the parade last year. Organized by Shawna Lutzow, who was volunteering at the center, and her fiancée Johanna Heineman-Pieper, the event was part of a series called “Conversation about Racism within Queer Communities.” Facilitated by Kiah Price, who identifies as a multiracial Black genderqueer lesbian and is a member of the International Socialist Organization, the presentation focused specifically on the history of LGBTQ Pride and relations between police and queer people, especially QTPOC.

Lutzow noted that the session was attended by OutReach Executive Director Steve Starkey and a few members of the board. She expressed frustration at what she felt was a lack of change in approach after the event.

“Johanna and I told OutReach that we are going to hold our conversations elsewhere since the conversations and content didn’t seem to help them move any further in the right direction,” Lutzow said. “We really wanted to help them get to where they want to be with being more supportive to QTPOC. So it was very disappointing when we learned that they were still going to allow police to march.”

A complex and fraught intersection

Prior to the final decision to remove police from the parade itself, OutReach had asked for and gotten a compromise from MPD Pride, the contingent of LGBTQ officers and allies that has marched in every parade since 2014. They agreed not appear in uniform or to bring along any squad cars or other official police vehicles.

Lt. Brian Chaney Austin, a member of MPD Pride who is himself an out gay, Black man, told a community listening session held the week before the parade that although he and his fellow LGBTQ-identified cops were personally upset by the decision, they understood and respected OutReach’s position.

“Although we wanted to take part,” he said, “we felt that we perhaps dropped the ball in relaying to the community, and particularly that aspect of community that had real valid concerns and fears as to who we are, number one, and as to what our purpose and mission is. I’ve tried to be upfront about our support of OutReach, I’ve tried to assuage some of the heartbreak about this…but I do not want any correlation between the police department and wanting some sort of boycott of the Pride parade. That is not where our position is. That is certainly not what any of us want to see happen.”

“Although we wanted to take part,” he said, “we felt that we perhaps dropped the ball in relaying to the community, and particularly that aspect of community that had real valid concerns and fears as to who we are, number one, and as to what our purpose and mission is. I’ve tried to be upfront about our support of OutReach, I’ve tried to assuage some of the heartbreak about this…but I do not want any correlation between the police department and wanting some sort of boycott of the Pride parade. That is not where our position is. That is certainly not what any of us want to see happen.”

Held at the Madison Central Library, the forum drew in close to 90 participants for a sometimes heated but largely respectful conversation about the issue.

Those who supported removing official, on-duty law enforcement from the parade cited ongoing concerns especially from queer and transgender LGBTQ+ people over feeling unsafe with armed police marching side-by-side with them.

“We need to shut up and listen to people of color and listen to and believe them about their experiences,” said Linda Ketcham, Executive Director of Madison Urban Ministry.

Racial disparities continue to negatively impact communities of color and LGBTQ+ people nationwide. Wisconsin has some of the country’s highest rates of incarceration for African American men, and in Madison, Blacks are arrested at more than 10 times the rate of whites. Milwaukee and Madison are some of the most segregated cities in the country. Half of the state’s “Black neighborhoods” are actually prisons. In Madison and Dane County, we continue to rank among the worst when it comes to racial disparities and inequality for everything from employment to graduate rates. Police have shot and killed unarmed Black men like Tony Robinson and Dontre Hamilton with little to no consequence.

Several of those present at the meeting expressed their own hurt and abuse at the hands of law enforcement, whether it was being profiled for their race, sexuality, or gender presentation, or actually being harassed or attacked. A woman who identified herself only as Christine, a member of the Madison Degenderettes and the TransLiberation Art Coalition, noted that she had been the “victim of police brutality myself, and I’m white. My experience was horrible, but I’ve heard much worse experiences from my friends who are not white.”

Others pushed back, arguing that the MPD has come a long way in its policies and procedures, and that asking even its LGBTQ-identified members not to march constituted discrimination and a step back from hard-won progress to serve openly.

Freda Harris, a Black woman and parent of a gay son, said she was sad to hear about the decision to remove cops from the Pride parade, and hoped that more communication would help lead to better solutions for the community. “I hate to see the community being torn apart because of concerns on one side and different concerns on the other. Talking to each other is hopefully going to bring us more together, or back together.”

The discussion remained mostly respectful, but did grow heated when certain pointed questions were posed. U.W. Madison Assistant Professor of Gender and Women’s Studies Sami Schalk asked, “I genuinely want to understand, particularly for white folks in the room, how this decision harms you? For me there’s a difference between ‘I feel unsafe when I see queer cops vs. I feel safe when I see cops.’ Being in this room speaking in front of all these people—many of whom are people who seem to be people who don’t’ support my community—fills my body with adrenaline. I want to understand the harm that’s being done to others. I want to hear from officers who are LGBTQ identified about how they feel about this.”

Madison native and bartender Jason Harwood interjected to note that he had once been helped by a gay cop and a straight cop after having withstood a physical attack. “They helped me get through all of that, including the trial afterwards, and not feel scared. Now they’re being asked not to participate.”

Another voice in the room countered with, “You were helped when your head was split open. Michael Brown was left in the street for hours.”

Schalk reiterated her question about how the decision caused harm. Chaney Austin spoke up on behalf of the officers, noting, “I live on both sides of the fence, y’all. It is quite challenging to be in the position I am…I grew up in Chicago. I had some bad experiences with members of law enforcement. From my perspective, I am trying to do something good with something that has been identified as broken. It is incredibly small and fragile baby steps that we’re taking in this mission. My hope is that we can continue to talk, my hope is that the very people who have really valid concerns and fears—I get it—I wanna talk. I wanna be able to sit down together in a small, potentially group environment where it’s potentially easier to have that dialogue. And then I can try to bring it back to my department to bring change.

“I understand the decision, I respect the heck out of it, I know we have more work to do,” he went on to say. “I don’t want the police to be what is fracturing our community. That will drive us absolutely to a point where we will not recover. But we accept that there are these fears—and ready to have these conversations and bring them back to decision makers.”

Another MPD Pride member, Officer Jodi Nelson, added her own thoughts. “We don’t want to take away from Pride, we want to support this event,” she said. “I am proud, I am a lesbian, and I have a partner. It took me a long time to get to this place. We are proud of who we are, we are proud of our group and the department. There are definitely things we can do to improve. We can’t always make the decisions of what is put out [to the public]. But we can be working behind the scenes. Whether we are agreeing at this table or not, I only think this kind of discussion will make our community better.”

Another MPD Pride member, Officer Jodi Nelson, added her own thoughts. “We don’t want to take away from Pride, we want to support this event,” she said. “I am proud, I am a lesbian, and I have a partner. It took me a long time to get to this place. We are proud of who we are, we are proud of our group and the department. There are definitely things we can do to improve. We can’t always make the decisions of what is put out [to the public]. But we can be working behind the scenes. Whether we are agreeing at this table or not, I only think this kind of discussion will make our community better.”

The MPD’s new transgender and nonbinary Standard Operating Procedure (SPO) was touted as one way in which LGBTQ officers on the force had worked with the community to create more inclusive policy. Police worked with OutReach’s Transgender Health Advocate, Ginger Baier, to create the SOP, which seeks to enshrine in official documentation how police should interact with and treat transgender and gender non-conforming people while on the job.

Chaney Austin told Our Lives that all officers had recently received a one-hour training regarding interactions with and education about the transgender community.

Several board members from OutReach attended the meeting as well, including Board President Michael Ruiz and Secretary Jill Nagler. “I know I hear a lot of vitriol from people who are against our decision,” Nagler said. “It makes me really sad, and it makes me scared to even say I’m with OutReach, so I can only imagine what QTPOC feel like in these situations. I’ve been on both sides. I grew up in a rural town where I was harassed, where I had a police officer call me a dyke. Those are strong, scary, powerful words. I moved to Madison and I hear stories, I see it, I’m not blind.

“I want to see individual officers marching off-duty, without the guns, without the badges. We want to get to know the humans behind the badge, behind the gun.”

In an interview with Our Lives, Chaney Austin laid out what he thought the challenges and goals were likely to be in the future.

“I don’t envy [OutReach’s] position, it’s really a challenging one to be in year in and year out. In the end we feel bad. We don’t want this to be a burden on this organization, we don’t want people to feel fearful of us. Our goal is really to humanize the badge and make sure people know who is actually marching in the parade. It is really the same people who you break bread with at the end of the day, the same people that go out to the same restaurants and bars as you do, the same people who have similar shared experiences as you do. Every part of the LGBTQ acronym is represented in our police department. We’re happy about that. We’re proud that we’ve been able to achieve that. That’s what we’re marching for. We’re not marching to say ‘Mission Accomplished.’ That ain’t happening. We’re saying we’re here, please know that we’re here in support, we are you, we’re part of the community, and we realize we have more work to do.”

Missteps & escalation

Over the course of July 31 and August 1, at least three queer people of color left comments on the official OutReach Pride Parade Facebook event page questioning the continued inclusion of police, and, in one case, calling OutReach’s decision racist. The comments were deleted at some point in the early morning hours of August 1, and commenting turned off entirely for the event.

That day, Kaci Sullivan, the organizer behind the TransLiberation Art Coalition, took to Facebook to call out what they perceived to be the silencing of QTPOC voices in the discussion. One of the people whose comments were deleted was TK Morton, a trans person of color involved in the TLAC who recently moved from Madison to Kansas. The two shared their frustrations and called out Starkey and others at OutReach about what had happened.

Those comments snowballed into a series of community discussions and arguments in various corners of social media. Lutzow and Heineman-Pieper started what was eventually called the Community Pride event in protest and began urging others to boycott the parade.

Letters were sent by protesters to every organization and business listed as an official sponsor of the OutReach Pride Parade, asking that they drop their support. Prior to OutReach’s final decision, according to Botsford, groups that had withdrawn from Pride are the WTHC, Orgullo Latinx LGBT+ of Dane County, Diverse & Resilient (which had already opted not to participate due to scheduling constraints), and Planned Parenthood Advocates of Wisconsin.

OutReach responded in the days following by releasing an official statement that attempted to explain the relationship between Pride and the police, as well as the decision to delete comments: “…in poor judgement, we removed posts and made the decision to prevent further discussion on the page. Our intent was to route those discussions to the upcoming MPD listening session, which OutReach requested. We sincerely apologize and acknowledge that we should have found a more transparent and thoughtful way to redirect this conversation.”

What cost Pride?

One of the accusations leveled at OutReach involved their mention of the MPD as a sponsor of the parade. Protesters have argued that OutReach was “prioritizing” fiscal support from police over the needs of queer and trans people of color.

Starkey shared the financial information from the event with Our Lives in an effort to offer clarity on the issue: “The MPD was a $100 sponsor this year. The fee they would have paid was $75 to have a contingent, so $25 was a sponsorship gift. The cost of hiring police in 2017 was $1,753. Our total fees paid to the City of Madison were $3,900. The total cost for the parade was $13,700.”

MPD Pride is a group made up predominantly of LGBTQ police officers and some straight allies. They participate while technically on duty, which is why, even in plainclothes, they will still carry badges and sidearms. MPD officers may earn MPPOA (straight time pay) by participation in community events like the Pride parade, according to their official union contract.

So…what now?

There are as many differing opinions around this issue as there are people in the community. On one end, the argument goes that police should have no role whatsoever—even for security—at a Pride event. Perhaps even holding a parade is too mainstream, and the community ought to revert back to its radical protest roots. Like Banks, many point to the origins of Pride in the U.S. as a series of anti-police riots, including Stonewall. There are ongoing issues with police at Pride events in various parts of the country, too, as well as institutionalized homophobia and racism within law enforcement as a whole.

On the other side, LGBTQ people who are themselves police (and their allies) wish to be included in an event celebrating all aspects of their identities. The argument in favor also includes the idea that it’s a sign of progress to have any police attend Pride in a friendly way (and to have openly LGBTQ officers), given the history of animosity between the groups and the hard work that has gone into making it possible to be out as a police officer. Others still can understand the need for police security but would rather they didn’t march in the parade, or if they do, out of uniform and without weapons.

Of course, it’s important to recognize that the modern LGBTQ Pride movement didn’t begin only in the U.S., but rather in a variety of ways in all parts of the world. The current movement is as diverse as its people and locales, with different issues impacting various communities in different ways.

The question for now seems to be, what real work can and should be done to make sure all members of the LGBTQ community are heard, valued, and supported? And how do you ensure that process without tearing down what few resources the community has in place for that support, especially in an era of increased hostility to LGBTQ people and people of color?

The answers will likely play out in the weeks, months, and years ahead. At very least, it’s clear that this year’s Pride controversy has caused a major and potentially irrevocable change in the conversation. —Emily Mills

0 Comments